COIN NOT ON POCKET

This coin really can not afford neither in size nor in weight.

This coin really can not afford neither in size nor in weight.

She appeared in the reign of Catherine I. True, her institution was not original.

In the first half of the 17th century, a new means of payment was introduced in Sweden: square plates. One daller, made of Swedish copper, weighed 1 kg 350 g. How not to understand respectable Swedish burghers, whose hearts and pockets undermined the heavy plates! But after all, the greatness of Sweden required a lot of silver, sailing away to endless wars …

Russia also had great needs for silver. Peter’s transformations, the creation of a new army and navy, the construction of St. Petersburg demanded a huge amount of money that was not so easy to shake out of the devastated and impoverished peasants, and even more so from the “loyal” boyars who looked with anguish at the new changes. Monastic values were a drop in the sea of military and administrative expenses.

By the way, how the clergy “contributed” to the transformation of Peter I can be seen from the following episode. To shelter church riches from the tsar, the monks of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra immured about 27 kg of gold and 272 kg of silver in the monastery wall. This treasure uselessly lay about 200 years.

With the death of Peter I, many questions remained unresolved in the finances of the Russian Empire. In order to cover the payment deficit to some extent, defective, so-called “Menshikovskie” money was issued.

At this time, in the Urals, red copper mining increased from year to year, and Catherine I’s financial advisers drew her attention to the possibility of replacing a silver coin with a Swedish one. This would greatly reduce the cost of the treasury to purchase ever-missing and expensive silver. As for copper itself, in the Urals it was much cheaper than that bought abroad, both Swedish and Hungarian.

On February 4, 1726, Catherine I issued a decree on minting at Siberian state-owned factories: “… from the finished, and which will melt copper, make red copper from the board and brand in the middle of the price and on every corner the coat of arms.”

In such boots, no winter is not terrible. Warm, comfortable, today for 1730 UAH

To this end, the Swedish master Deichman was sent to the Urals to organize the monetary processing. That is how coins – boards were born, to have which in the collection is the dream of every coin collector collecting Russian coins.

In the same decree it was said that the chasing of boards should be at the rate of 10 rubles. on the pud of copper, that is, without offsetting the price of a coin of the conversion cost.

This was the copper price that existed at the time.

Compared with the rest of the copper coin, which was minted at the rate of 40 rubles. per pud, chasing slabs at the rate of 10 rubles. on the pud of copper – a significant step forward in streamlining monetary circulation.

Copper coins in the people went to an enormous amount, and a good half of them were fake because the cost of a piece of copper going to make a coin was much cheaper than the price indicated on it. The striking discrepancy between the practical cost of copper coins and the cost of silver was aggravated by the fact that the sample of pure silver in large Russian silver coins was the highest in Europe. This led to the fact that, despite the strictest bans, large silver systematically went abroad, and the more affluent segments of the population hid silver coins.

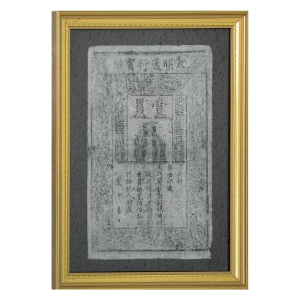

The minting of copper plates took place at the Ekaterininburg Mint. The coins were issued in the form of copper plates, on the corners of which the state emblems were beaten out, and in the middle in the circle – the price of the coin, the year of issue and the place of minting.

The ruble coin was issued weighing 1.6 kg. It was minted twice – in 1725 and 1726.

Poltina weighing 800 was produced only in 1726.

But half-a-half was minted in 1725 and in 1726, and this year 4 of them were released. It weighed 400 g. For three years (1725–1727) weighing 160 g, hryvnias were issued. In 1726, 6 of them were released.

5 kopecks and 1 kopeck were minted in 1726, with 5 kopeks having 3 varieties, and kopek was in 2 types.

It makes little sense to dwell on the varieties of these square coins. For example, the hryvnia of 1726 differed from each other either by the number of feathers in the tail of the eagle (3 and 5), or by the size of the image of St. George, or instead of St. George on the eagle’s chest was a monogram. Making fun of one of the editions of the Russian society of numismatists, the well-known Russian numismatist Oreshnikov very sharply responded to the “direction” among some collectors who collected coins according to the “special type of eagle”, “large crowns”, “special tail of the eagle with feathers bent up”.